giving

|

Offering feedback is one method of learning about what is working and what could be improved. Offering feedback is not about judging skills, knowledge, and understanding; neither is it about hurting feelings. Often our habit is to say what we like publicly and what we dislike privately and to someone else. This makes it very difficult to learn from our experience and mistakes. It also creates a climate of distrust. Offering feedback is a tool, which should be used strategically. Because we work in organizations that must think critically, we sometimes have difficulty discerning when critical thinking is helpful and when it becomes important to offer support, regardless of the circumstances. Approval and affirmation are as important as critical thinking; both should be offered at appropriate times. To give constructive feedback:

|

ANDMaisha Z. Johnson's article on 3 Things to Consider When Choosing Between Calling Someone Out or Calling Them In.

Maisha Z. Johnson's article on 6 Signs Your Call-Out Isn't Actually About Accountability. Loretta Ross' article on Calling In Call-Out Culture. |

change team & caucuses

One way to facilitate a race equity process in your organization or community is through the creation of a change team and caucuses. The change team is responsible for leading the race equity change, including the formation of clear race equity goals and processes to achieve them. The caucuses are spaces for People of Color and white people (and/or other identity groups) to support the work of the change team.

the role of the

|

The role of caucuses is:

|

|

Change team members are people who:

Their job is to develop a group of people who will work together to reach explicitly stated goals in line with the organization’s mission. This involves working with others to:

|

the role of the

|

|

The role of the change team is:

1. to lead and organize the process towards becoming an anti- racist social change organization and help move people into actively supporting (or at least avoid resisting) the changes necessary to move the organization towards that vision

2. to lead and organize a process to evaluate the organization as it is now 3. to lead a process to help the organization vision what it would look like as an anti-racist social change organization 4. to lead a process to establish specific, clear, and meaningful goals for reaching the vision 5. to build community and move the organization to collective action

6. think like an organizer in helping the organization move toward its goals

|

change team

|

|

|

Use this checklist about once every two or three months to make sure your change team is staying on track:

|

change team

|

change agent

|

|

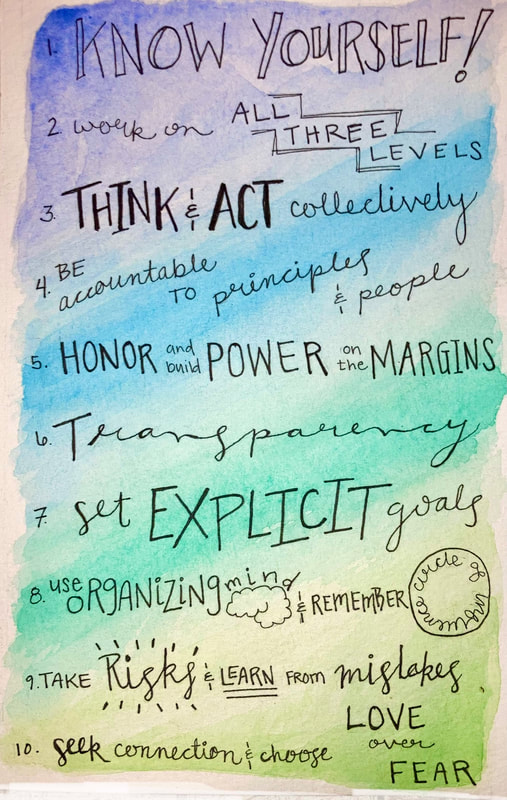

racIAL equity principles

organizing mindThis principle is grounded in the wisdom of experienced and effective community organizers. To use organizing mind means that we begin by looking around to see who is with us, who shares our desires and our vision. We then build relationships with those people. So, for example, if we find one other person to work with, then the two of us fine another 2 people, then the four of us find another 4 people and so on. Organizing mind is based on the idea of “each one reach one” (with thanks to Sharon Martinas of the Challenging White Supremacy Workshop) in ways that build relationships, community, solidarity, and movements.

Using organizing mind helps us to focus on who and what is within our reach so we can build a larger group of people with whom to work and play and fight for social justice. This principle is closely tied to the work of Stephen Covey (The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, 1992), which is its turn based on the work of Viktor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning, 2006). Covey speaks to the importance of focusing on our circle of concern, which helps us build our individual and collective power and effectiveness. Frankl, a Jewish psychotherapist, was imprisoned in a series of concentration camps during WWII and spent much of his time observing the behavior of his fellow prisoners and the Nazi prison guards. He noticed how some prisoners were more “free” than their guards because of how they used the space between what happened to them and how they chose to respond. Frankl then defined “freedom” as that space between what happens to us and how we choose to respond. Covey then took this idea and applied it to the circles of concern and influence. The circle of concern includes the wide range of concerns that a person or community has, including everything from a (public) health problem to the threat of war (what happens to us). The circle of influence includes those concerns that we can do something about (how we choose to respond). Proactively focusing on our circle of influence magnifies it; as a result our power and effectiveness build. Reactively focusing on concerns that are not within our circle of influence, on what’s not working or on what others can or should be doing, makes us much less effective. It also leads us to blame and/or wait for others to change before we act, which leads to a sense of frustration and powerlessness. The connection to organizing mind is that too often we focus on people who are too far away from us (our circle of concern) rather than on those who are closer who we haven’t yet organized to work with us (our circle of influence). When we complain “we’re preaching to the choir,” our response is “yes, we need to start organizing the choir.” When we complain about the apathy or disinterest of those we are trying to reach, this is often a sign we are too focused on who is not yet with us and we need to refocus on who is, even if it’s only one or two other people. explicit goalsWe all know how easy it is to “talk the talk” – and the talk of racial justice is deeply compelling. This principle asks us to tie the talk of social justice to explicit goals so that people and communities have a clear sense of what social justice looks like up close and personal. When people in communities or institutions make a race equity commitment, they often have little to no idea of what that commitment means in terms of their role, their job, or their responsibility. Those leading the change must build a team that can help people identify what racial justice looks like in their sphere of influence, whether it is working for a policy goal to stop deportations or an internal organizational goal to insure clear communication across language and cultural differences.

We can use transparency to help people understand complexity and nuance. For example, if we are trying to land on a strategy for taking action, rather than argue that one strategy is the “best” or “right” one when there is disagreement, we can be transparent about the tensions involved in making a choice. Transparency is really useful when we find we are caught between conflicting values or options; rather than force ourselves to take a position, we can make the tension transparent and work collectively to make choices about how to face the tension and learn from the choices.

|

These 10 principles for taking action were developed as a result of dRworks' experience working with organizations and communities

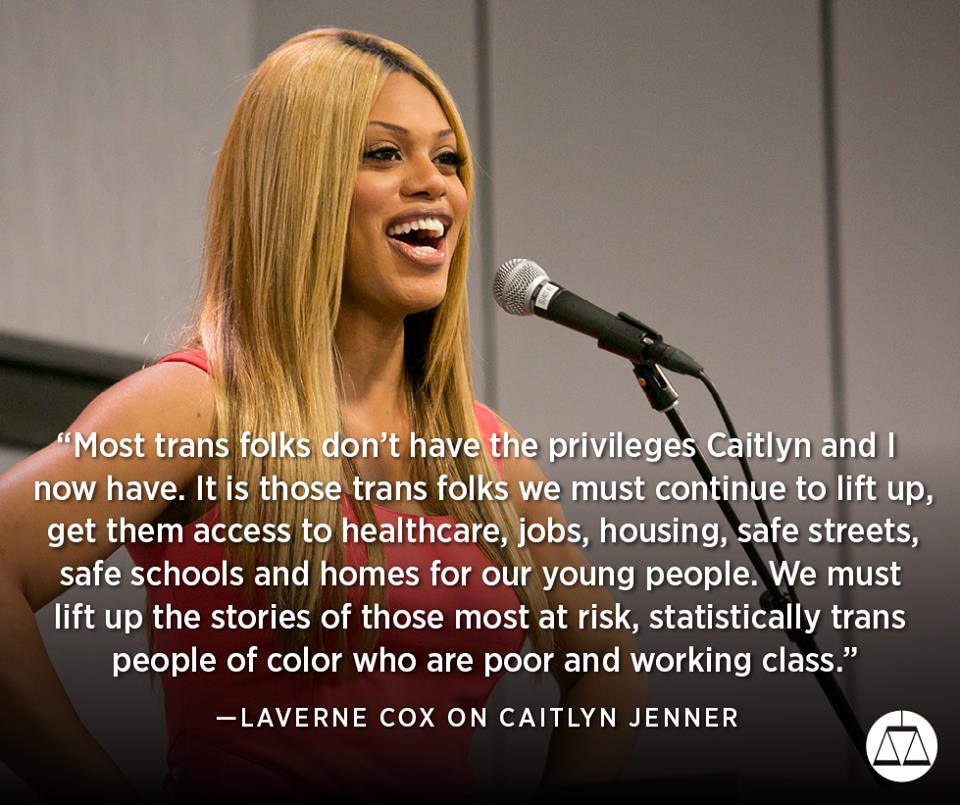

for over a decade. Honor & BUILD

| |||||||

| Accountability | |

| File Size: | 64 kb |

| File Type: | |

work on all

three levels

Racism shows up on three levels:

personal/interpersonal, institutional, and cultural. This means that liberation shows up on all three as well. Working for racial justice means we need to work on each of the three levels. If our organization or community offers expertise and skills in two of the three, we can intentionally partner with organizations and communities working on the other. For example, an organizing initiative

focused on teachers in a mid-size southern city is offering yoga classes for their members, led by yoga teachers committed to tying their practice to the vision of building a strong public education for all.

We must avoid being so focused on one aspect of liberation that we ignore or even disdain the others. We are all familiar with the individual committed to fighting for justice in the world while sacrificing relationships with friends or family or, in some cases, engaging in violence towards family members as a release for unexamined feelings. We are too familiar with social justice organizations that exploit the people

personal/interpersonal, institutional, and cultural. This means that liberation shows up on all three as well. Working for racial justice means we need to work on each of the three levels. If our organization or community offers expertise and skills in two of the three, we can intentionally partner with organizations and communities working on the other. For example, an organizing initiative

focused on teachers in a mid-size southern city is offering yoga classes for their members, led by yoga teachers committed to tying their practice to the vision of building a strong public education for all.

We must avoid being so focused on one aspect of liberation that we ignore or even disdain the others. We are all familiar with the individual committed to fighting for justice in the world while sacrificing relationships with friends or family or, in some cases, engaging in violence towards family members as a release for unexamined feelings. We are too familiar with social justice organizations that exploit the people

take risks & learn from your mistakes

This culture often teaches us that to make a mistake is to be a mistake. Maurice Mitchell, one of the leaders of Black Lives Matter, is making the point that we will inevitably make mistakes and our anxiety about that does not serve us or the movement. Failure to take risks because we are afraid of failure or our own vulnerability does not serve us or others. We can, of course, take risks more wisely through collaboration and accountability, which avoids putting others at risk without their knowledge. Denying that we made a mistake also does not serve us or others. Failure to learn from our mistakes is the only real mistake we can make.

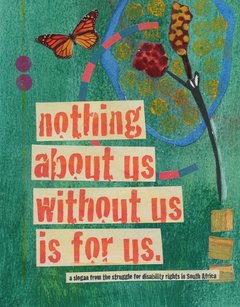

think & act

collectively &

collaboratively

We live in a culture enraptured by the idea of the single hero riding in on a white horse (or a inter-galactic spaceship) to save the day. We are all of us raised by institutions (schools, the media, religious institutions) that reinforce the idea of individual achievement and heroism. The reality is that our history and particularly the history of the arc of social justice is a history of movements. This principle is based on the idea that we save and are saved by each other.

By design, the dominant culture insures that we have a very weak collective impulse; the collective impulse that people and communities held originally (Indigenous nations and cultures) or brought with them from other countries and cultures has been systematically erased in the service of racism. This means that we have to teach each other and ourselves to collaborate and act collectively. We can look for guidance to those people and communities whose resilience has preserved that impulse.

Acting collaboratively and collectively means that we build strong and authentic relationships that enable us to act in concert with each other from a place of wisdom collaboratively and collectively gathered. It also means that we learn from our mistakes rather than pretend we never make them.

By design, the dominant culture insures that we have a very weak collective impulse; the collective impulse that people and communities held originally (Indigenous nations and cultures) or brought with them from other countries and cultures has been systematically erased in the service of racism. This means that we have to teach each other and ourselves to collaborate and act collectively. We can look for guidance to those people and communities whose resilience has preserved that impulse.

Acting collaboratively and collectively means that we build strong and authentic relationships that enable us to act in concert with each other from a place of wisdom collaboratively and collectively gathered. It also means that we learn from our mistakes rather than pretend we never make them.

KNOW YOURSELF

Taking action for racial justice requires a level of self-awareness that allows us to be clear about what we are called to do, what we know how to do, and where we need to develop. Another way of thinking about this is to know our strengths, our weaknesses, our opportunities for growth, and our challenges. Knowing ourselves means that we can show up more appropriately and effectively in whatever the work is, avoid taking on tasks we are not equipped to do well, ask for help when needed, and admit when we don’t know what we’re doing or claim our skills gracefully when we do. White supremacy and racism affects all of us; we internalize cultural messages about our worth or lack of worth and often act on those without realizing it. We also tend to reproduce dominant culture habits of leadership and power hoarding, individualism, and either/or thinking. We may be dealing with severe trauma related to oppression. We may be addicted to a culture of critique, where all we know to do is point out what is not working or how others need to change.

Doing our personal work so that we can show up for racial justice is, ironically, a collective practice. We need to support each other as we work to build on our amazing strengths – our power, our commitment, our kindness, our empathy, our bravery, our keen intelligence, our sense of humor, our ability to connect the dots, our creativity, our critical thinking, our ability to take risks and make mistakes. We also need to support each other as we work to address the effects of trauma and the dis-ease associated with white supremacy and racism. We do this by calling each other in rather than out. We do this by holding a number of contradicitons, including that we are both very different as a result of our life experience and we are also interdependent as a growing community seeking and working for justice. We do this by taking responsibility for ourselves and how we show up to facilitate movement building.

Doing our personal work so that we can show up for racial justice is, ironically, a collective practice. We need to support each other as we work to build on our amazing strengths – our power, our commitment, our kindness, our empathy, our bravery, our keen intelligence, our sense of humor, our ability to connect the dots, our creativity, our critical thinking, our ability to take risks and make mistakes. We also need to support each other as we work to address the effects of trauma and the dis-ease associated with white supremacy and racism. We do this by calling each other in rather than out. We do this by holding a number of contradicitons, including that we are both very different as a result of our life experience and we are also interdependent as a growing community seeking and working for justice. We do this by taking responsibility for ourselves and how we show up to facilitate movement building.

doing the work of the organization. Similarly, we also know individuals who spend so much time engaged in personal reflection that they become lost to the movement and we know organizations who focus on personal work without tying that work to movement building.

An example of work on all three levels is an emerging national network of racial justice activism. The network is grounding leadership in a practice called somatics, which is designed to support transformational change rooted in the belief that we benefit from understanding how trauma impacts us. The work of understanding our own personal relationship to trauma is done as a collective practice in the service of developing our individual and collective capacity to facilitate the day-to-day work of movement building.

An example of work on all three levels is an emerging national network of racial justice activism. The network is grounding leadership in a practice called somatics, which is designed to support transformational change rooted in the belief that we benefit from understanding how trauma impacts us. The work of understanding our own personal relationship to trauma is done as a collective practice in the service of developing our individual and collective capacity to facilitate the day-to-day work of movement building.

seek connection

We live in a culture of fear. Fear shuts down our ability to be creative, compassionate, and brave; fear also divides us and pits us against each other. Notice when fear shows up, name it, and seek ways to feel it, address it, and choose a way that builds connection and relationship. Ground your actions in a desire for connection; choose love (not that it’s always easy to know what love is in any situation) and ask yourself: what would build connection here? Relationship? Love?

race equity

|

You can use this tool to determine goals and/or to analyze the implications of a key decision related to a goal:

Step 1: Identify key outcomes (content).

Step 2: Involve stakeholders.

Step 3: Advance opportunity. Minimize harm. (process)

Step 4: Determine benefit and burden.

Step 5: Evaluate. Reflect. Raise racial awareness.

Step 6: Report. Revise.

|

other tools

|

The Showing Up For Justice Political Education website offers resources for white people on Taking Action and another on How to Show Up.

|

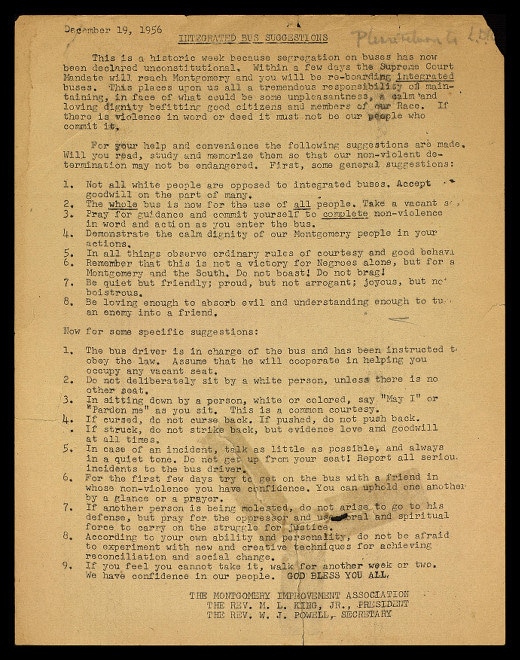

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s list of 16 suggestions for African-Americans riding newly integrated buses (1956).

Click here for more.